Educating immigrant communities about parasitic infections

Communicating important health information to the public can be difficult if there is a language barrier. Professor Sheena Cruickshank is tackling this through her award-winning engagement activities with non-native speakers of English.

Parasitic infections may not immediately seem like a crucial topic for immigrants to Britain to learn about.

However, it was research into this type of infection that eventually led to a commendation in the University's 2019 social responsibility awards for Professor Sheena Cruickshank and her colleagues working within infection and immunity, who want to break down language barriers and confusion around scientific language to pass on important health information.

For Sheena, immunology is a lifelong passion that grew out of a love of science originating in childhood visits to rock pools with her brother. As expected for a child growing up with a keen interest in wildlife, zoology was always at the forefront of her mind. That was until her brother was diagnosed with cancer.

"When my brother became ill I was very angry," Sheena says. "Ultimately, I became curious as to why he was ill and that was when I became fascinated about disease and our immune systems, and decided I would study immunology."

A successful career in immunology has followed, working at Manchester since 2007 and picking up a series of awards along the way, including a Better World Award and a Making a Difference Award for Social Responsibility in 2017, and a Royal Society of Biology Communicator of the Year award in 2013.

Sheena Cruickshank

Sheena is a senior lecturer and researcher in immunology at The University of Manchester

Discovering a language barrier

The Making a Difference commendation for Outstanding Teaching Innovation in Social Responsibility came on the back of a project which aims to educate immigrant communities based in Greater Manchester about infections and how to avoid them, so they are better equipped to make key decisions about their own health.

For the communities to fully engage with the science content, it was necessary to teach them the relevant scientific and healthcare jargon.

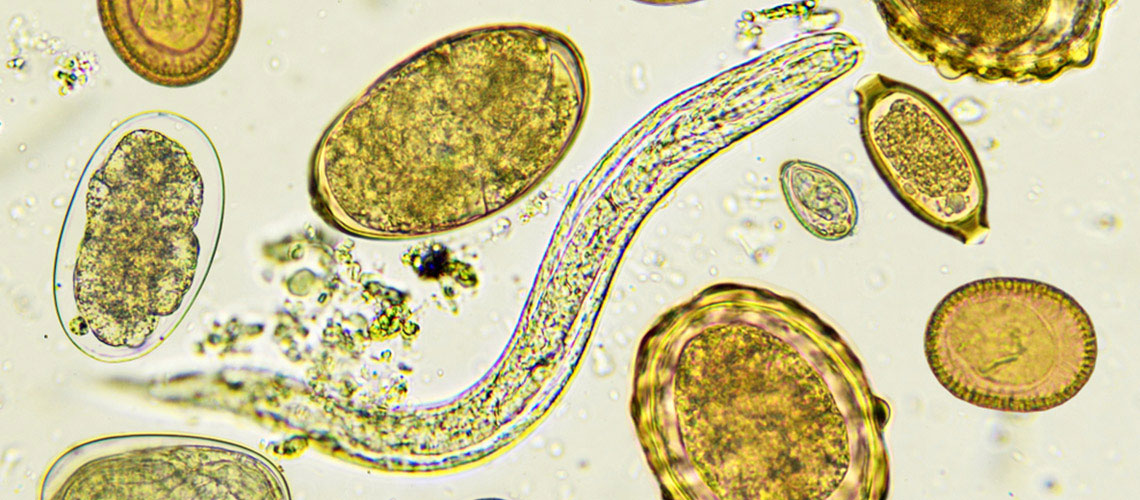

"This project came about when we were working on parasitic infections," Sheena says.

"A lot of the infections we look at aren't common in this country anymore, such as round worm or whipworm, and we wanted to learn from people who had personal experiences with these infections whilst sharing the research we do into the infections.

"For us, a good opportunity to do that was to work with immigrant communities who originated from countries where these infections were still commonplace."

By working with these communities, the research group realised there was a sticking point around scientific language, irrespective of how good their English might be. This was something that Sheena wanted to explore further.

“Medical and scientific language is just weird, and they understandably weren't grasping it," Sheena explains.

"It was always going to be a barrier when it came to us having two-way, meaningful conversations, so I set up a collaborative project with an English teacher who specialised in teaching English to non-English speakers."

This resulted in working with PhD students on the BBSRC Doctoral Training Partnership programme to develop a suite of resources to teach people about infections, while teaching them the correct English terms at the same time.

"It's essentially a science lesson and an English lesson rolled into one," Sheena says.

Taking action

The classes were trialled at Bolton College and in community centres nearby, and after positive initial feedback, interest in both teaching and learning grew.

More teachers wanted to get involved and class sizes started to expand, allowing Sheena to take more of a back seat as time went on.

"The classes are really mixed and we can have as many as 18 different nationalities in one class, with both older adults and teenagers attending," Sheena says.

"We have to have English as the main language, but we really encourage people to compare the English words to words in their own language, which results in fantastic discussion.

"In the first year, I was heavily involved with the teaching and was out with some DTP students delivering the content alongside the English teachers, but since the second year, we've reduced our workload to the point now where we are just there for guidance."

Expanding the project

All was going well in Bolton, but the next natural step was to expand the project and make the content available for everyone to access. As a result, the E-Learning team at the University were tasked with creating an online, easily accessible hub for the content.

After months of hard work, the website was launched in December 2018, with feedback so far being overwhelmingly positive.

"It was really important to us that our lessons were freely accessible online, so that anyone can use them, and the E-Learning team have made that possible," Sheena says.

"My favourite part is the dictionary that they've made for us. In lessons, we give the students a set of words that we want them to use repeatedly throughout the lesson for both oral and written work. The aim is for them to gain an understanding of what the words mean and how to use them in sentences by the end of the lesson.

"The E-Learning team have managed to transform this into an online dictionary featuring all of the words, with playback options and example sentences for further support. It really is fantastic and they deserve a lot of credit for the Making a Difference Award nomination."

As well as the resources being made available online, medical students have used some of the resources on trips to Madagascar, while members of staff have been able to use them in other public engagement activities, such as exhibitions and activities in schools.

The future

Looking ahead, Sheena is aiming to expand this project, as well as integrating its themes into other projects.

The website will continue to grow but, on the whole, Sheena is keen to ensure that more people continue to be better informed about their health and the available treatment options.

"My main aim is make science and healthcare accessible to everyone," Sheena says.

"A lot of the information here is about self-care and managing your own health, and if you don't have access to that sort of information, how are you going to look after yourself as well as you can?

"There's loads of misinformation passed around, and when you don't involve people with decisions about their healthcare, you do end up with really bad situations happening.

"Luckily for us, we've been able to empower certain communities and provide them with a vital knowledge base, and we will look to continue to do that."

A two-way collaboration

For Professor Keavney, the notion of a two-way exchange of ideas sits at the heart of DGEMBE.

"We have worked very hard as a team to ensure that the high-value aspects of DGEMBE take place in South Africa – not just the sample collection, which takes so much work, but also the technical aspects of the analysis," he explains. "If researchers need to be taught in Manchester, they're taught here, and then they return to South Africa. So, there's true capacity development."

Another consequence of DGEMBE has been the establishment of a zebrafish research facility in Cape Town, a first for the city and among the first such facilities in South Africa. This is led by Associate Professor Gasnat Shaboodien, who spent time with Dr Kasher in Manchester to learn the fundamentals of setting up such a facility. It is hoped that the facility will help power work not only by cardiovascular researchers, but also by researchers working in other fields, such as neurology.

"The amount of support we received from staff and students at Manchester through DGEMBE has been phenomenal," Associate Professor Shaboodien says.

"The DGEMBE partnership has delivered beyond our expectations, opening up avenues for new partnering initiatives, such as with Dr Philip Day at the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology," adds Dr Engel, Associate Professor in UCT's Department of Medicine and co-investigator on the grant from UCT.

Find out more about social responsibility in the Faculty.